Another bad news about ocean pollution. A study by the three French institutes Ifremer, the University of Bordeaux and the IRD (a public research institution) reveals that the surface water of the Atlantic Ocean is twice as polluted by cellulose fibres as it is by microplastics. This study, based on measurements taken from an offshore race boat, also shows that the North Atlantic is more affected by plastic pollution than the South Atlantic and questions the dynamics of the subtropical gyre (area with a high concentration of microplastics) since the ocean pollution levels measured there are lower than expected.

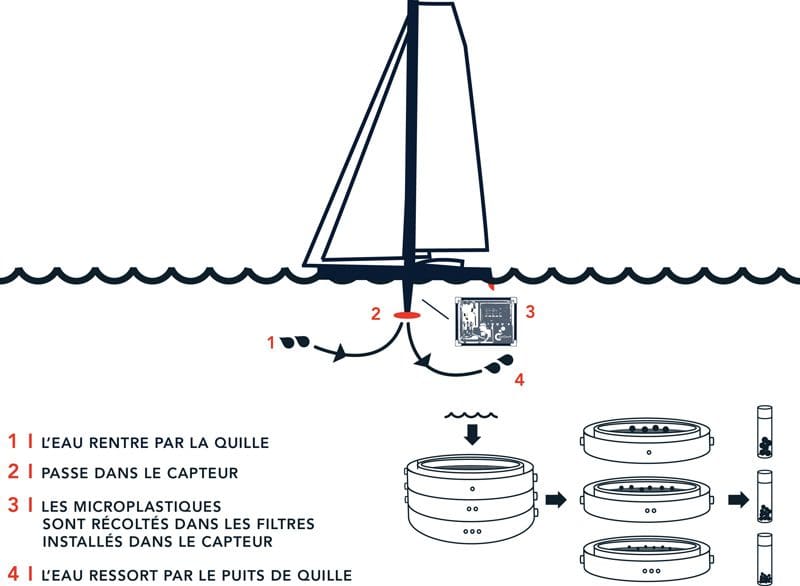

During the last ‘Vendée Globe’, a single-handed round the world yacht race, French skipper Fabrice Amedeo collected 53 samples using the microplastics sensor fitted aboard his Nexans – Art & Fenêtres sailboat. The various teams led by Catherine Dreanno, a researcher at Ifremer Brest, LDCM lab, Jérôme Cachot, professor at the University of Bordeaux, EPOC lab, Sophie Lecomte, Director of Research at CNRS, CBMN lab and Christophe Maes, Head of IRD research, LOPS lab, have just completed the analysis of 300 µm mesh filters. They give us the low-down on their initial analysis.

The first observation focuses on the concentration and the wide variety of shapes, sizes, colours and kinds of particles and fibres (ranging between 0.3 and 5 mm) in the samples taken, which contained twice as many cellulose fibres as microplastics (MP). “Cellulose fibres are present in virtually all the samples collected (92.5% of samples), in contrast to microplastics, where solely 64% of samples contain at least one piece of microplastic, explains Catherine Dreanno. These results support the theory that there is widespread contamination of the seawater offshore by anthropogenic particles created from the breaking up of plastics or washing clothes.”

Through spectroscopic analysis it is possible to work out that the fragments of microplastics studied are predominantly (45%) polyethylene (PE), particularly that used in plastic bags and food wrap, as well as polyethylene terephthalate (PET), notably that used in plastic bottles.

It’s important to note that in the case of microplastics, like that of cellulose fibres, which colonise our oceans, there is an acute problem with the additives used by manufacturers to modify the properties of these materials: colouring them, making them more hard-wearing, rigid or, on the contrary, more flexible. “As the material ages, these additives end up coming away from the medium which, in this case, is cellulose fibre or a particle of microplastic, and dissolving in the ocean or being released into organisms’ digestive tracts if these particles are ingested”, adds Sophie Lecomte.

A sea change between the South Atlantic and the North Atlantic

The most surprising element in the researchers’ findings is that this initial study of offshore surface waters reveals a real difference between the South Atlantic and the North Atlantic: a certain number of samples collected in the south do not contain microplastics and generally they contain less than in the north.

“However, we should have found some as Fabrice Amedeo navigated the subtropical South Atlantic Gyre, an area renowned for its massive concentration of this material. This unique set of data casts doubt then over the internal dynamics of the gyre. We’ll have to wait and see how the smallest fragments, those collected using 100 and 30 µm filters, are divided up and distributed in the water column”, explains Christophe Maes.

The samples in the 100 µm and 30 µm filters are in the process of being analyzed, along with those from the last Transat Jacques Vabre between Le Havre and Brazil, which will enable the mapping of microplastic ocean pollution in the North Atlantic, together with a more in-depth study into the difference in concentration between the South and North. Upcoming sea passages will enable an even deeper understanding of the Atlantic Ocean too. Indeed, Fabrice Amedeo will this year participate in the Vendée – Arctique – Les Sables (a race between France and Iceland) and the Route du Rhum (Saint-Malo – Pointe-à-Pitre): during these sea passages, the microplastics sensor, which is funded with the support of the Onet Group, will be in operation 24/7.

It’s worth pointing out that this far-reaching project is a truly unprecedented opportunity to collect and analyze microplastics of different size grades, which are present in the surface waters of the ocean, an area that currently has little data available about it. “We need to better quantify and characterize the pollution of offshore waters to find out where it comes from, as well as to better gauge the risks associated with this pollution for oceanic marine ecosystems”, explains Jérôme Cachot. On the whole, it’s a relatively new playing field for the scientific community.

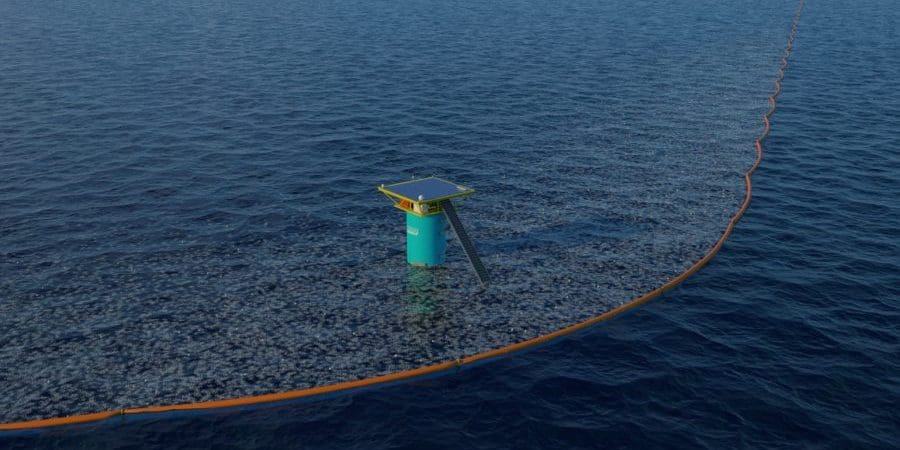

Mapping seawater in an offshore environment is a challenge, as it covers vast geographical areas about which we have precious little data on plastic pollution. Given that we cannot take action in all places, at the same time, it’s important to identify the main sources of plastic pollution to find out where we need to take action first. There’s a pile of information doing the rounds about the pollution of the oceans. We’re here to set the record straight and verify the science behind it. This report on offshore oceanic pollution should give rise to new policies and regulations aimed at limiting these sources of pollution, as well as measuring the effectiveness of these policies and noting how pollution evolves over time.”