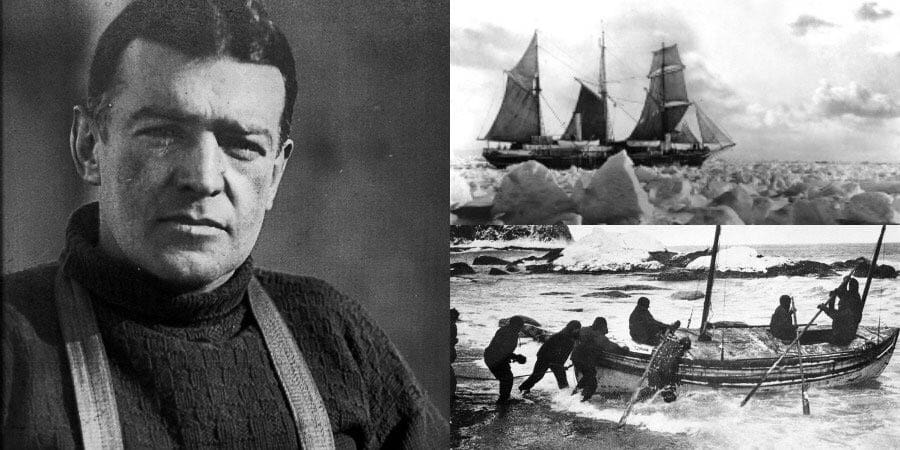

Three times, vainly, he challenged the South Pole. His ship was crushed by ice. He never gave up: sailing for eight hundred miles on a seven meters lifeboat in Antarctic Seas, he saved all 27 members of his crew. This is the story of the greatest explorer of all time, Ernest Henry Shackleton.

“For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton”.

This declaration was made by Raymond Priestley: geologist, geographer, British explorer, and also president of the Royal Geographical Society. Was he exaggerating? Not at all. Ernest Shackleton is, even today, the symbol of a man who could accomplish the impossible.

Ernest Henry Shackleton, from Irish countryside to the Pacific

Born in 1874 in Kilkea House, Ireland, at the age of sixteen, Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton enlisted on a ship of the British merchant navy, running away from the medical studies his father wanted him to pursue. Ten years of travel between the Pacific and Indian Oceans were enough for him to realize that the merchant navy would not give him the opportunity him to satisfy his ambitions.

His desire for fame and wealth then pushed him to pursue a career as an explorer. To start he joined the Antarctic expedition organized by the Royal Geographical Society and led by Robert Falcon Scott, another huge name in the exploration of the poles.

A live donkey is better than a dead lion…

The goal of the expedition was to be the first to reach the South Pole. Scott and Shackleton almost made it: they only had about 480 miles left to the South Pole before they had to give up. A breaking point was created between the two, according to some caused by Ernest’s ever increasing popularity among the members of the expedition. This fracture was at the base of Scott’s decision to send his colleague back to England, citing health reasons.

Four years passed before Shackleton was able to return to the South Pole, this time at the head of an expedition. Aboard the three-master Nimrod, and with the financial help of the Australia and New Zealand governments, the ship reached Ross Island in the spring of 1907, where they set up base camp (still visible today). The expedition’s official purpose was to analyze the mineralogy of Antarctica, but the real purpose was always the same: to be the first to reach the South Pole.

Shackleton felt strong and well-prepared thanks to the experience he had gained in the previous expedition. However, preparations soon proved to be once again insufficient. The members of the expedition were sailors and not expert-skiers. The decision to use Manchurian ponies was counterproductive: so much so that they had to be progressively put down. Despite all this, the members of the expedition managed to get just 180 kilometers from the South Pole.

Here, Shackleton demonstrated a great critical capacity and a remarkable ability to assess the situation: even though their objective was so close, he realized that if they went on, their return would be impossible. So he decided to return to the base camp. To those who asked him to explain his decision, he always replied: “A live donkey is better than a dead lion“.

Epic endurance

For three years Ernest Henry Shackleton held the record of having been the closest to reach the South Pole. The record was then torn from him when first Roald Amundsen, and then Scott, reached it before him. The only remaining prestigious conquest was the crossing of the Antarctic continent.

And so on August 1, 1914, on the eve of the outbreak of World War I, the three-master Endurance set off with twenty-eight men aboard. Launched in Norway from the Framnaes Schipyard shipyards, it was a tall sailing ship 44 meters long and was equipped with a single propeller engine with an output of around 350 horsepower, which allowed an average speed of 10 knots, specifically designed for Arctic exploration.

But the conditions of the ice shelf were prohibitive and particularly extensive: on January 19th Endurance got stuck in an icepack. “Our position on the morning of the 19th was lat. 76°34’S, long. 31°30’W. The weather was good, but it was impossible to advance. Overnight the ice surrounded the ship, and clear sea could not be seen from the bridge,” Shackleton wrote in his diary.

The men spent the long austral winter on the ship, but on October 27th they abandoned Endurance, and a month later it was completely destroyed by the pressure of the ice. Shackleton transferred the crew to the icepack in an emergency camp called “Ocean Camp”, where they remained until December 29th. They then moved, towing three lifeboats, to an icepack that they called “Patience Camp”. There has never been a more appropriate name.

Stuck on the ice

The crew was forced to wait months before they could move again. In April 1916, the men noticed that the ice was beginning to break up, and boarded the lifeboats. Ernest Henry Shackleton had already planned where to direct the group. The best destination would have been Desolation Island, about 160 miles west. Other possible destinations were the two most neighboring islands, Elephant and Clarence.

Once on board, the crew was constantly wet and couldn’t light a fire to keep warm or to melt ice (essential for drinking). Shackleton realized he had no other choice: he had to reach dry land as soon as possible. After seven days at sea all three boats reached Elephant Island, whose surface is almost completely covered with snow and ice and is relentlessly beaten by strong winds. If Shackleton’s ability to keep the crew alive thus far was remarkable, it is at this point that the expedition became legendary.

Eight hundred miles on a seven-meter lifeboat

Shackleton understood that they had to depart again, and quickly, for South Georgia and its whaling fleet base. A decision that at first seemed crazy: it meant dealing with over 800 miles of one of the most dangerous oceans of the world aboard the James Caird, one of the seven-meter lifeboats that had been saved before Endurance’s destruction.

“A live donkey is better than a dead lion“.

To prepare the boat they raised the freeboard, reinforced the keel, and built a makeshift bridge out of wood and fabric soaked in oil and seal blood to make it waterproof. To determine the route, all the crew had was a stop watch and a sextant. Considering their minimal chances, Ernest Henry Shackleton decided to load enough food for only four weeks: unless he had reached the destination within that time frame, it would likely mean that they had drowned and, worse, been lost in the southern seas.

Everyone is saved!

On April 24, 1916 Shackleton and a five of his chosen men left Elephant Island. They faced huge waves and wind gusts estimated at around 100 km/h, and after fifteen days of sailing, finally came within sight of South Georgia. A storm forced them to fight for nine hours just to get close to land, but they finally managed to land on May 10th. The whaling stations, however, were on the other side of the island.

Circumnavigating it was not even a consideration due to the strong winds and rocky, dangerous coastline. But the inland was no joke, either: the area had never been explored and was mostly covered by icy mountains. Along with two crew members, Shackleton transformed his shoes into crampons by putting nails in the soles. With no other equipment, they managed to cross the over 30 kilometers between their landing point and the Stromness base in just 36 hours. They were greeted with disbelief by the whalers, who perhaps thought they were ghosts…

Organizing the rescue operations for the 22 crewmen that had remained on Elephant Island wasn’t easy: the UK was busy fighting World War I, and Shackleton realized that he wouldn’t get any help from home. So he sought help from South America. On August 30th, four months after his departure from Elephant Island, the Irish explorer managed to reach all 22 castaways aboard a Chilean naval vessel.

Ernest Henry Shackleton returned home

It’s not merely Ernest Henry Shackleton’s incredible journey sailing the James Caird that puts him in the record book of explorers, but the fact that despite the incredible hardships he faced, not a single member of the expedition was lost. Still unsatisfied from his prior experiences, Shackleton set sail for Antarctica once again in 1921 on the ship Quest.

By that point he was a legend, and on the day of his departure from London he was sent off by a cheering crowd. But in the port of Grytvyken, South Georgia (call it destiny), he had a heart attack and died. While his body was being taken to England, his wife took measures to ensure that it was instead buried in the Grytvyken cemetery. His real home.